Farmers search for a way out of deep debt

Published on 30 August 2015

Writer : Jitsiree Thongnoi

The vicious cycle of people on the land borrowing money from banks or loan sharks to stay afloat shows little sign of coming to an end.

It was the third time this month that Suphan Buri rice farmer Boonchu Maneewong, 59, travelled to Bangkok to plead with government officials for help with crippling debt.

the cost of business: When rains are normal, Suphan Buri farmers can get good returns. As rice has become a global commodity, there is pressure to adopt a higher level of technology.

In the past week, Ms Boonchu and several other farmers from her area rose early to catch a van from their home town at dawn in order to arrive at the Agriculture Ministry on Ratchadamnoen Avenue by 9am. As the offices opened for the day, farmers, aged mostly in their fifties, waited in halls and stairwells.

After an hour, they were told to go upstairs to the “Farmers Help Centre”. As they went in, an official was taking a phone call informing him that the farmers were on the way.

“I need a government official to go to Suphan Buri and negotiate with the lenders,” Ms Boonchu said on behalf of 15 farmers to the official after he hung up the phone.

The official said he didn’t know if that was possible. “The case is not yet in court and even if it is, it has to follow legal procedures,” he replied, sounding eager to send the group off to another government ministry.

His reluctance was understandable. There will never be enough government officials to intervene to help farmers cope with the massive debts they are carrying. Provincial Administration Department figures released earlier this month showed 21.59 billion baht debt in the non-formal loan sector and 366.7 billion baht in the formal system.

Ms Boonchu was directed to the office of the Bangkok Metropolitan Administration, where one official said he might intervene. It seems totally illogical that a Suphan Buri farmer would ask a Bangkok city officer for help, but in their desperation many farmers are turning to any official to try and intervene on their behalf.

This year, almost every Suphan Buri farmer needs official intervention when it comes to their debt problems. Severe drought throughout the year has made it impossible for them to harvest their paddy during the 120-day mid-year rice season. Many of them are already carrying long-standing debt.

With interest mounting, sometimes by the day, either from banks or loan sharks, the drought becomes like rubbing salt into their wounds. “Nobody grew rice this year. I know it didn’t rain, but usually there would be some water reserves in the local canals. But this year there was none and I don’t know why,” said Ms Boonchu.

FROM LAND OWNER TO RENTER

Ms Boonchu lives in Amphoe Doembang Nangbuat in Suphan Buri where the majority of the roughly 80,000 residents are rice farmers. She and her husband and three children decided to open a car garage almost 20 years ago to try and boost their income. “In 1996, I took a 600,000 baht loan from a commercial bank to open a garage,” she recalled.

The family hoped the money from the business could support them from season to season and also provide extra income to help fund the children’s education. But Ms Boonchu’s plan turned out differently.

In 2002, a bank took legal action against her after she started missing payments. It was the beginning of her changing from a land owner to a renter. “I had about 10 rai of land, given to me by my parents to grow rice,” she explained.

“But when I was sued, I mortgaged five rai to my sister in order to be able to find money to pay back some part of the debt and the interest.”

making the case: Boonchu Maneewong struggled to control her debt.

Another five rai was sold to her brother for 500,000 baht. It went to the bank, but because of the accumulated interest and loan penalties, only 100,000 baht was paid off the principal on the loan. The bank was charging interest rates of up to 18%.

In the following years, Ms Boonchu “rented” back the farmland she used to own from her siblings. Instead of paying them money, she agreed to give them 20 containers of rice a year. This would give her a chance to pay back the bank and continue supporting her family.

But in 2004, Ms Boonchu received a final warning from the bank, after her accumulated debts had risen to 1.4 million baht, more than double the original loan. The bank confiscated her house, but after her case received coverage in the press, she was allowed to buy it back for 500,000 baht.

Ms Boonchu was forced to turn to loan sharks, who agreed to loan her the money as long as she repaid within a year plus 15% interest.

Over the years, Ms Boonchu was able to bring back her now 550,000 baht loan into the formal system by mortgaging the house with the Government Housing Bank on a 30-year mortgage.

NO LAND OF MINE

Sangwian Wanwiroj, 60, is a farmer and labourer from Amphoe Don Chedi, Suphan Buri, and is reluctant to admit she is in debt.

She has never taken loans from commercial or government banks or loan sharks. However, she constantly struggles to repay money from a village fund allocated to each family, which she receives payments from every year.

“For the past six or seven years, I was allocated 30,000 baht from the village fund scheme. But every year, before the next allocation is made, I have to pay back the loan from the earlier year, 30,000 baht plus a little more than 1,000 baht in interest.”

Ms Sangwian travelled to Bangkok with Ms Boonchu because she is about to be evicted from the land she has stayed on illegally for the past 22 years.

“The new owner of the land bought it five to six years ago, but I was allowed to stay on the land by the previous owner who passed away.”

Ms Sangwian presented a handwritten plea to the Agriculture Ministry official. In it, she begged the official to help her “negotiate in the purchase of the property I stay on. Three families live in three buildings on the land, and I and my relatives are losing a shelter to live in,” she said in the letter.

She later told Spectrum, “Many years ago, I spent the 30,000 baht village fund to buy watermelons to sell in front of my house. Later, the earnings were reduced to only a few hundred baht a day so I stopped.

“Now I am a construction labourer earning 300 baht a day. I cannot lose my land because I have no place else to live. At least I can still eat the vegetables I grow on my land.”

FLOATING LAND TRANSFER

Kanyawee Khanthonglor, 48, took a 1.1 million baht loan against her 12-rai shrimp farm, which she “mortgaged” to a loan shark. She wanted the extra funds to improve her business operations.

But under what’s called a “floating land transfer”, Ms Kanyawee’s current debt is almost double the amount.

According to Ms Boonchu, a floating land transfer contract is reached where the land is put up as a guarantee. The debtor and lender reach an agreement on the loan amount, the interest rate and a timeframe for the loan to be repaid, often two years.

But Ms Boonchu said most of the borrowers only meet the interest repayments in order to keep the contract open. When the contract expires and the loan has not been paid off, the debtor is then at the mercy of the loan shark. Often the loan amount is increased, sometimes to the market value of the property.

In the case of Ms Kanyawee, who did not meet the first “contract” deadline, the loan amount was increased by one million baht. She now owes 2.1 million baht and if she does not meet the terms of the second agreement, the lender has threatened to sell the property.

“My land is a square shape and has road access,” she told Spectrum at the Agriculture Ministry offices. “It could be rented out for 4,000 baht per rai per month, but the sale price per rai could go up to 400,000 baht.”

In her letter, she said, “I ask you to find me a loan source with a low interest rate so I can buy back my land and continue to pay off debts because me and my children are still capable of that.”

FARMING NOT SUSTAINABLE

Pongtip Samrarnjit, executive director of NGO group Local Act, links debt issues with the problem of land ownership. Failure to hold legal possession of the land means farmers lose access to income and education opportunities.

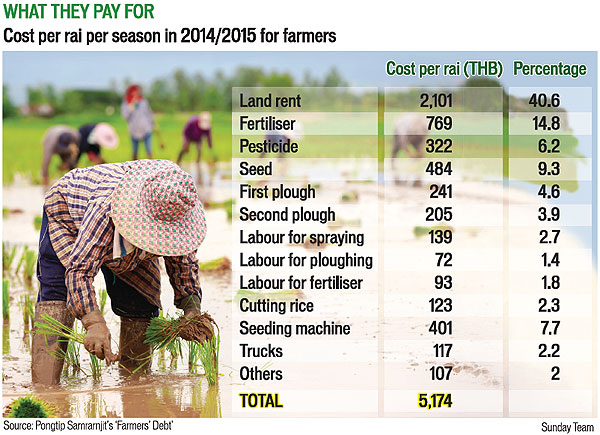

The second reason is that as rice has become a global commodity over the past century, farmers have been pushed to adopt practices where high productivity heavily depends on fertiliser and machinery. High productivity also opened ways for rice buyers — the middlemen — to come between farmers and the markets. As farmers failed to unite to support one another, they fell prey to big agriculture.

“Farmers are the rice-producing mechanism, but the profits belong to other interest groups,” Ms Pongtip said.

“Interest groups form stronger, more powerful associations — exporters, millers, buyers, even seed or fertiliser producers.

“At times, rice buyers become the lenders as they lend the money and require crops as payment. If farmers can no longer produce rice, they become meaningless and useless.

“The situation in the Central region of Thailand is more volatile, as seen from the effect of the drought. Without water, farmers cannot apply for more loans because they cannot use the rice produce as an advanced guarantee.”

Ms Pongtip said in general, farmers are indebted to three lenders — the Bank for Agriculture and Agricultural Cooperatives, the commercial banks and loan sharks.

“Major formal lenders, which are the BACC and the local agricultural co-ops, are not very helpful in solving farmers’ debt issues,” she said.

“Loans from the BACC start with an interest rate of 7% with a ceiling of 13%. In my opinion, in order for the loan to be really helpful, the interest rate should stay between 4% and 5%. Commercial banks’ interest rates on loans vary, but they can reach as high as 25% depending on the amount of the loan, the size of land or the price of the property farmers put up as a guarantee.”

Ms Pongtip’s view is echoed by Manus Namlert, 68, a farmer from Suphan Buri who said loan schemes create, rather than reduce, debt.

“Most of the farmers in debt who mortgage their land are not in the process of buying back the land through debt payment, which is the reason they turn to the system to begin with. Farmers are made to go through schemes which force them to take out further loans, even in small sums each time.

“If farmers are taking out loans from the BACC and they run out of commodities or property credit, they are advised to apply for a credit card with the bank as a means of having quick cash. They only end up being more indebted.”

Ms Pongtip said the BACC is now the biggest lender for farmers. In 2012, 29 million rai of agricultural land was mortgaged with the bank.

GROWERS ARE ALSO CONSUMERS

Ms Pongtip said the economic stimulus package proposed by newly-appointed Deputy Prime Minister Somkid Jatusripitak is merely a short-term solution for declining domestic consumption. Ms Pongtip said the rice subsidy should not be seen as a populist policy, but instead as “basic welfare” in the agriculture sector.

“The rice price went down to 4-6,000 baht per tonne, whereas a price of 8-10,000 baht should be guaranteed,” he said.

“In the medium-term, the government should find a solution to problems such as debt clearance with NPL [non-performing loan] status for the past 10 years or a debt amount below 10,000 baht.”

In the long term, the government “should look into fairness in the land-rent system and the whole production line to make it really sustainable”, Ms Pongtip said.

In her study, Ms Pongtip interviewed 87 farming households in Ang Thong province in the Central region and found 18% earned 10,000-50,000 baht annually, 24% earned 50,000-100,000 baht and 17% earned 150,000-200,000 baht.

The highest monthly expenditure was food at an average of 4,229 baht per household. The study found 86% of farming households did not eat the rice they produced, but instead bought it for consumption.

STRIKING DEBT NUMBERS

Late last month, Prime Minister Prayut Chan-o-cha provided a general outline of a rural debt-relief scheme where the Agriculture, Interior, Justice and Finance ministries would cooperate.

He cited a July 10 survey which showed total debt in the agriculture sector of 400 billion baht. Of the six million workers in the agricultural sector, 1.6 million carried debt at an average of 240,000 baht each.

The coordinated plans include offering legal aid, negotiation and debt compromise as well as the government taking over the debt.

The Agriculture Ministry’s Farmers Help Centre, which Ms Boonchu and her peers visited last week, will be the main coordination office. Cases involving intimidation by loan sharks will be handled by the Justice Ministry’s Rights and Liberties Protection Department and the Department of Legal Execution.

Other non-urgent debts will be handled by the independent Office of Farmer’s Reconstruction and Development Fund.

In her study, Ms Pongtip traced the FRD’s performance from 2006 to last year and found 28,304 farmers’ debts totalling more than 5.7 billion baht had been paid off. After the FRD pays off debt, the property must be transferred to the office. At present, 17,532 land deeds, amounting to 125,062 rai of farmland, have been transferred. Land transferred to the FRD is not auctioned off and farmers maintain the right to work on that land during the pay-off period.

Even though Ms Boonchu’s debt is now under control, the failure to grow crops this year provides her with a certain level of instability. Her group of about 15 farmers are planning to petition as many government officials as they can for help, including the PM’s Office, the Finance Ministry’s permanent secretary and the Public Service Office.

They are hoping that some of the officials will visit Suphan Buri and talk with the loan sharks to find a positive outcome for all sides.

“I live in the house I own now,” Ms Boonchu said. “But for farming I have to rent the land, which used to be mine, from my sister. Even though I am a renter, I will never be a debtor again.”

cash crop: Many farmers in Suphan Buri have had to bargain with banks or loan sharks to cover the cost of planting rice crops. Some also give away crops in lieu of money.

มูลนิธิชีวิตไท (Local Act)

129/250 หมู่บ้านเพอร์เฟคเพลส รัตนาธิเบศร์ ถนนไทรม้า ต.บางรักน้อย อ.เมือง จ.นนทบุรี 11000

โทรศัพท์: 02 040 9969 | 090 178 7508

E-mail : This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

ผู้เข้าชม

11245397

วันนี้

เมื่อวานนี้

สัปดาห์นี้

เดือนนี้

ทั้งหมด

4759

4960

22782

167070

11245397

Your IP: 216.73.216.127

2026-02-25 11:49